The Wagner Tuba: A History, William Melton

William Melton, The Wagner Tuba: A History. Edition Ebenos, Aachen, Germany, 2008. ISBN 978-3-9808379-1-0. €24. Related Website

This book’s multi-coloured cover showing a Wagner Tuba floating in the sky above a tiny Festspielhaus set against distant mountains provides a striking contrast to the more mundane covers of most other books about musical instruments. On the back we read “The History of the Wagner Tuba: One Part of the History of Gebr. Alexander,” though in fact Melton’s book is not a panegyric for that particular maker but something far more objective. He has ranged far and wide for both primary and secondary sources, although the reader will not find information on acoustics, materials or dimensions. Here we read biographies of obscure composers and instrument makers, lists of members of horn sections and details of Wagner’s domestic life. The book is printed on heavy art paper, giving opportunities for photographs, including a 15-page “Gallery of Wagner Tubas by Contemporary Manufacturers.”

Melton (American-born and now a horn player in Sinfonie Orchester Aachen) has chosen to deal with an unusual subject, always a doubling instrument and therefore never the one most familiar to its player, reviled for problems with intonation and prone to have its music performed on other instruments. The Wagner tuba was invented by the composer to bridge the gap in the brass section between the sounds of trombones and horns. Its profile lies between that of the valved bugle-horn (the euphonium) and French horn and it is played by horn players using a similar mouthpiece and rotary-valves operated by the left hand. Wagner groups them in sections of four, two tenors in F and two basses in Bb. Pretty well all of the preceding statements have to be qualified by the word “usually.” As Melton relates, there were many existing instruments capable of inspiring Wagner in the design of the tubas. Some of them, especially Cerveny’s cornon of 1844 which Wagner may have heard in Dresden, were remarkably similar and all of them were tried and tested. However, as in so many aspects of his life and work, Wagner was determined to go his own way. The author’s suggestions as to why Wagner initially chose to ask Alexander, at the time renowned only for the manufacture of woodwinds (notably clarinets), to make his new brass instruments rather than Moritz, builder of the first basstuba, would have been welcome.

A generous number of music examples (48 in all) and end-notes (totalling 811: there are 14 references in the first sentence alone) contribute to the comprehensive nature of the book. The author usefully explores the extraordinary number of notations used by Wagner and hence adopted by later composers. Wagner quite often changes the instruments’ notation within the same work and in some instances the results are so ambiguous that performers have still to reach agreement about the pitch of certain passages. Paradoxically, in this case the German, of a nationality renowned for its logical thinking, was at odds with his Belgian contemporary Sax, working in Paris, whose system of notation for saxhorns and saxophones remains a model of simplicity and practicality.

Amongst a smattering of errors is the statement that the ‘new bass tuba [was] termed “contrabass tuba” by Wagner’. In fact they were two different instruments: the original basstuba, pitched in F, was specified by Wagner in some of his earlier works, but following the invention of the contrabass tuba in BBb or CC (probably by Cerveny in 1845) he specified this instrument from Das Rheingold (1853-54) onwards. He treated the two instruments quite differently. Similarly, the author alters Wagner’s own term ‘contrabass trombone’ to ‘bass trombone’. The contrabass is of lower pitch. In the opera pit, a team of trumpets (including bass trumpet) and trombones (including contrabass) sits at one extremity while horns, tubas and contrabass tuba sit at the other, providing contrasting timbres.

The claim that Wieprecht and Moritz led the way for the appearance of ‘the myriad family of bugle horns . . . cornet, fluegelhorn, alto horn, baritone and euphonium)’ by their invention of the basstuba in 1835 reverses the actual chronology. The basstuba could only be constructed after methods of making its large valves were devised. The statement that Moritz’s firm was in 1862 accorded the title Court Instrument Maker is curious as Moritz is described thus in the basstuba patent of 1835, almost 30 years earlier.

As stated here, Sommer of Weimar developed the euphonium, but it is not true to state that it was later called the baritone horn: this instrument already existed and was then, as later, different in profile from the euphonium. To consider that tubas may have been contemplated by Janacek for the Sinfonietta is to overlook the fact that the first movement, in which two tenor tubas are prominent, was inspired by a military band: euphoniums are always used here. A euphonium also plays tenor tuba in Holst’s Planets; this British composer had been an orchestral trombonist and knew the instrument that he wanted.

After the exploration of possible inspirations for the tubas and an exposition of their use by Wagner, the following chapters are bound to be something of an anti-climax. ‘Wagner’s Heirs’ tend to be mainly obscure composers trying to make a reputation through gargantuan works, although Bruckner and Stravinsky stand out. ‘Modern Voices’ continues this theme, showing that fascination with the tubas wound down after World War I. ‘Revival’ charts the use of the instruments since about 1960, when different musical idioms have been widely explored, often including unusual instruments. Jazz and particularly film music, which sometimes utilised as many as eight tubas (it was claimed in 2002 that one out of every four American film scores used the instruments), gave employment to versatile horn-players. But how often are the tubas heard as individual voices, or as a section playing in four parts as Wagner envisaged?

There are some things left unsaid in this book. The drawing of the cross-section of a Lur mouthpiece is not shown alongside a Wagner tuba mouthpiece so that we might compare and contrast. Information about the instruments pictured (including those in the Gallery of Wagner tubas) is restricted to the names of the maker and the model. Even manufacturers’ leaflets give information on important aspects like bore and bell diameter. Some of these instruments seem to have remarkably similar profiles to valved bugle horns. It is tantalizing not to have at least basic technical data.

Melton confirms that at their first public appearance, in 1874, the tubas (a set made by Ottensteiner of Munich) were still far from technically perfect. Moritz delivered a set in 1877, but when Richter later conducted excerpts from the Ring in London Munich players were imported, probably playing instruments by Ottensteiner. By 1890 Alexander had made a definitive set, delivered to Bayreuth for opera performances also conducted by Richter. Other makers, including those in a number of European countries, have sought to make tubas which avoid the problems for players resulting from poor intonation.

It is notable that when Henry Wood was planning his Wagner performances in 1895, following Richter’s concerts in London including tubas, he commissioned a set of instruments by Mahillon. (At the Parisian Lamoureux concerts in 1888 Besson cornophones played the parts.) Of saxhorn shape, with four piston-valves and large mouthpiece receivers, this reviewer was privileged to join three Covent Garden musicians in playing on them the tubas passages from the Ring. These experienced opera house players expressed their satisfaction with the tone, tuning and security of the instruments. For performances at the Norwich Festival in 1908 Wood rehearsed four members of the Kettering Rifles Band playing them at intervals over a period of two years. However, in New York, owing to the number of immigrant German musicians authentic tubas were heard as early as 1886.

The final development in the Wagner Tuba story concerns attempts to make a satisfactory double instrument, after the fashion of the double horn. The author and others quoted here claim that this results in a loss of contrast in timbre between the F and Bb instruments. But those who read this book should then turn to a recent article that complements much of what is said here, and in at least one instance contradicts it.

Appearing in Galpin Society Journal LXIII (May 2010, pages 143-158) is an article by Lisa Norman, Arnold Myers and Murray Campbell entitled “Wagner Tubas and Related Instruments: An Acoustical Comparison.” This is “an initial foray into the acoustical identity of the Wagner tuba, providing a broad comparison with related instruments, and also looking more closely at what influences the response, timbre and intonation of a specific instrument.” The instruments include tubas by Alexander, Mahillon, Moritz and Schopper alongside cornophones and baritones. There is a great deal to be learnt here from the input impedance curves for the various instruments (and also a euphonium and trombone for purposes of comparison) along with comparative bore profiles of a significant selection. Information is provided in the form of graphs and tables making it easy to compare the data for each instrument. This is then expanded in the text.

Surprisingly, acoustical tests did not show particular problems in tuning, although overall more recent instruments performed better. Most interestingly, the double Wagner Tuba showed the greatest variation in brassy timbre between the two sides of the instrument. These scientific conclusions fail to confirm two of the characteristics of the instruments most commonly perceived by players: poor tuning and the double instrument’s lack of differentiation between F and Bb sides. Perhaps it is fair to conclude that these perceptions result from the individual musician’s lack of familiarity with instruments which in many cases are brought out of the opera house’s store-rooms only occasionally.

-- Clifford Bevan

Bruce Boyd Raeburn. New Orleans Style and the Writing of American Jazz History. Ann Arbor:

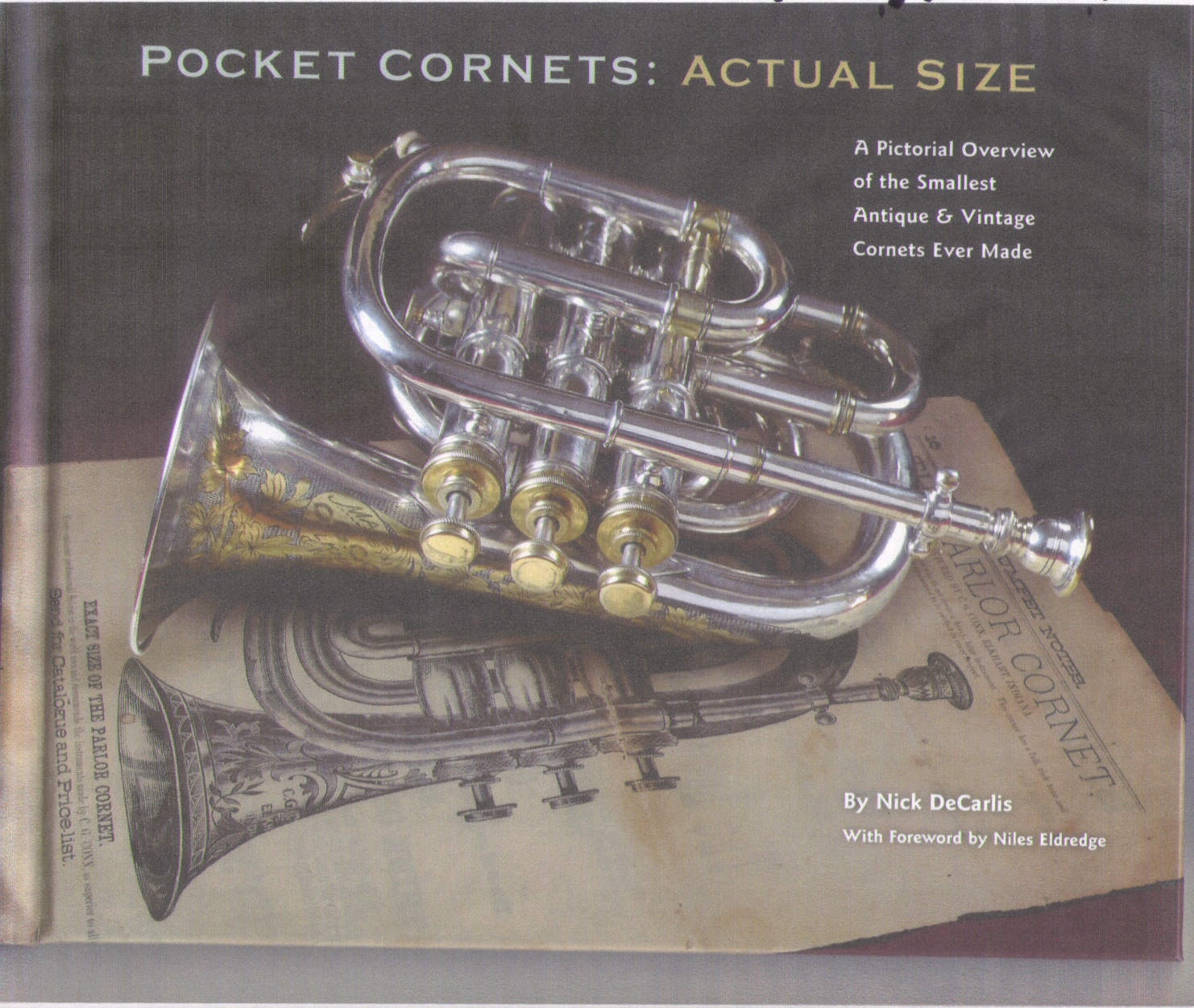

Bruce Boyd Raeburn. New Orleans Style and the Writing of American Jazz History. Ann Arbor:  Pocket Cornets: Actual Size. A Pictorial Overview of the Smallest Antique & Vintage Cornets Ever Made,. By Nick DeCarlis. Published by the author, 2009. 75 pages hardcover. Information:

Pocket Cornets: Actual Size. A Pictorial Overview of the Smallest Antique & Vintage Cornets Ever Made,. By Nick DeCarlis. Published by the author, 2009. 75 pages hardcover. Information:  The Trumpet Book by Gabriele Cassone. Zecchini Editore

The Trumpet Book by Gabriele Cassone. Zecchini Editore

Edward H. Tarr, The Trumpet, Trans. S.E. Plank, Revised and Enlarged Limited Edition.

Edward H. Tarr, The Trumpet, Trans. S.E. Plank, Revised and Enlarged Limited Edition.  Kurt Dietrich, Jazz 'Bones: The World of the Jazz Trombone;

Kurt Dietrich, Jazz 'Bones: The World of the Jazz Trombone;